Postoperative Ileus Risk Calculator

Your Estimated Risk

0% High Risk

Estimated recovery time: 3 days

Reduce opioids to under 30 MME to lower POI risk to 18%.

What Is Postoperative Ileus, and Why Do Opioids Make It Worse?

After surgery, your gut should start working again within a day or two. But for many patients, it doesn’t. This delay in bowel movement is called postoperative ileus (POI). It’s not a blockage - your intestines aren’t physically clogged. Instead, they just stop moving normally. You feel bloated, nauseous, can’t eat or drink, and don’t pass gas or stool for days. It’s uncomfortable, frustrating, and it keeps you in the hospital longer.

Opioids are a big reason why. Pain meds like morphine, oxycodone, and fentanyl work great for pain, but they also slow down your digestive system. They bind to mu-opioid receptors in your gut, shutting down the muscle contractions that push food and waste along. Studies show these drugs can reduce colonic motility by up to 70%. Even small doses - like 5 to 10 mg of morphine per hour - can delay gastric emptying by 50% to 200%.

It’s not just the drugs you’re given in the hospital. Your body releases its own opioids during surgery as part of the stress response. That means even if you didn’t get any pain meds, your gut is still being hit with natural opioids. Combine that with surgical trauma, inflammation, and reduced movement, and you’ve got the perfect storm for POI.

How Bad Is It? Real Numbers Behind the Problem

Postoperative ileus isn’t just a minor inconvenience. It’s expensive and dangerous. In the U.S., POI adds 2 to 3 days to hospital stays on average. That costs the system about $1.6 billion every year. For patients, it means more pain, more risk of infection, and more time away from work or family.

Here’s what patients actually experience: 46% to 81% develop hard, dry stools. Nearly 60% report straining during bowel movements. Over 40% feel bloated or have abdominal distension. Some even get more acid reflux. These symptoms usually show up within 24 to 72 hours after surgery.

One study of 1,247 surgical patients found that those who got more than 50 morphine milligram equivalents (MME) in the first 48 hours had 3.2 times more severe bloating and took over 3 days longer to have their first bowel movement than those who got less than 20 MME. That’s not a small difference - it’s the difference between going home on day 3 or day 6.

Traditional Treatments Don’t Work Well

For years, doctors relied on a few basic tools: nothing by mouth, IV fluids, and a nasogastric tube to suck out stomach contents. But here’s the truth - those don’t fix the problem. A Cochrane review found nasogastric tubes only reduced POI duration by 12% compared to standard care. That’s barely better than doing nothing.

Waiting for your gut to wake up on its own isn’t a strategy - it’s just patience. And patience doesn’t help when you’re in pain, scared, and stuck in a hospital bed. You need active solutions, not passive waiting.

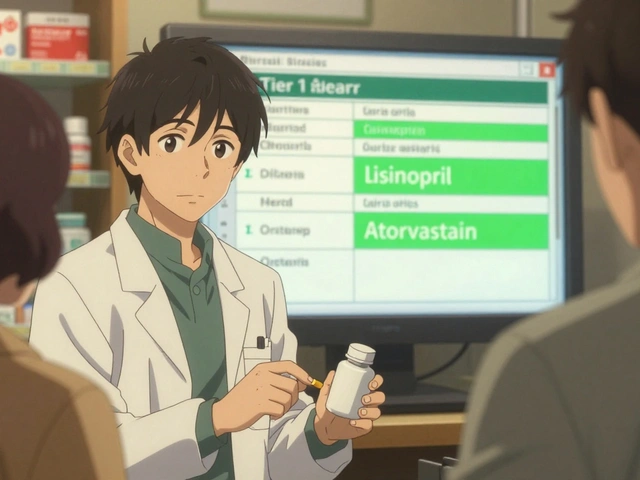

What Actually Works: Multimodal Analgesia and Early Movement

The best way to prevent POI isn’t to treat it after it happens - it’s to stop it before it starts. The key is reducing opioid use without sacrificing pain control. That’s called multimodal analgesia.

Here’s how it works in practice:

- Start acetaminophen (1g IV) before surgery - not after.

- Add ketorolac (30mg IV) if you don’t have kidney issues or bleeding risks.

- Use regional anesthesia like epidurals or nerve blocks whenever possible. One study showed epidurals cut POI duration from 5.2 days to 3.8 days in orthopedic patients.

- Limit total opioid use to under 30 MME in the first 24 hours. Studies show this drops POI incidence from 30% to 18%.

And don’t forget movement. Getting up and walking is one of the most powerful tools you have. Dr. Michael Camilleri from Mayo Clinic says walking within 4 hours of surgery cuts POI duration by 22 hours on average. Even simple things like sitting up, turning in bed, or chewing gum (yes, gum) help. Chewing signals your brain that food is coming, which triggers gut motility. Nurses in some hospitals now schedule gum-chewing four times a day - and it’s working.

When Opioids Are Still Needed: Peripheral Antagonists

Sometimes, you can’t avoid opioids. Major surgeries, severe trauma, or patients with high pain scores need them. That’s where peripheral opioid receptor antagonists come in.

These drugs - like alvimopan and methylnaltrexone - block opioids in the gut without affecting pain relief in the brain. They’re like a filter: they let the pain meds work where you need them (your spine and brain), but stop them from slowing your intestines.

Alvimopan (given orally) reduces time to bowel recovery by 18 to 24 hours after abdominal surgery. Methylnaltrexone (given as a shot) works even faster in opioid-tolerant patients, cutting recovery time by 30% to 40%. These aren’t magic bullets - they cost $120 to $150 per dose - but for high-risk patients, the benefit is clear.

They’re not for everyone. Don’t use them if you have a bowel obstruction (which happens in less than 0.5% of cases). And they’re not cost-effective for low-risk patients having minor procedures. But for someone having a colon resection or major joint replacement? They’re worth it.

What Hospitals Are Doing Right (and Wrong)

The best hospitals don’t just treat POI - they prevent it with structured protocols. These are called ERAS (Enhanced Recovery After Surgery) bundles.

Successful programs include:

- Daily POI rounds where surgeons, anesthesiologists, and nurses check bowel function together.

- Standardized tracking: time to first flatus (goal: under 72 hours), time to first bowel movement (goal: under 96 hours), ability to drink 1,000 mL of fluid within 24 hours.

- Clear opioid thresholds: if a patient gets more than 40 MME in 24 hours, they get a peripheral antagonist automatically.

Programs with full adoption see 85% to 90% compliance within a year. They reduce hospital stays by 1.8 days and save $2,300 per patient.

But many hospitals still struggle. Anesthesia teams resist changing opioid habits. Nurses aren’t trained to push early mobility. Rural hospitals? Only 28% have any formal POI prevention plan. That’s why patients in academic centers recover in 3.2 days on average, while those in rural facilities wait 5.1 days.

The Future: AI, Microbiomes, and New Drugs

Science is moving fast. Researchers are testing AI models that predict who’s at highest risk for POI - using 27 pre-op factors like age, BMI, medications, and surgery type. One Mayo Clinic trial got 86% accuracy. Imagine knowing before surgery that you’re likely to get POI - so you can start prevention before you even wake up.

Other ideas? Fecal microbiome transplants for stubborn cases. Early data shows a 40% improvement in gut motility. And there’s a new version of alvimopan in Phase III trials - this time, designed to be safer and longer-lasting.

One day, we might have implants that slowly release opioid blockers for days after surgery. But for now, the tools we have - multimodal pain control, early walking, and targeted antagonists - are enough to make a real difference.

What You Can Do as a Patient

If you’re facing surgery, ask these questions:

- Will you use regional anesthesia instead of general if possible?

- Can I get acetaminophen or ketorolac before and after surgery?

- What’s the plan to limit my opioid use?

- Will I be helped to walk within 4 hours after surgery?

- Will I be offered chewing gum?

Don’t be afraid to speak up. POI isn’t inevitable. It’s a side effect of how we manage pain - and we can do better.

What Happens If You Stop Opioids Too Fast?

One risk of cutting opioids too quickly is withdrawal. Some patients - especially those on long-term opioids before surgery - get symptoms like nausea, sweating, anxiety, and muscle aches when switched from IV to oral meds too fast. In one study, 12% of patients had withdrawal symptoms lasting 3 to 4 days. That’s why transitions need to be planned. Don’t just stop the IV and hand them a pill. Taper slowly, use non-opioid backups, and monitor closely.

Final Thought: It’s Not Just About Pain - It’s About Recovery

Pain control matters. But so does getting your gut back online. The goal isn’t to eliminate opioids - it’s to use them smarter. When you combine the right pain meds with movement, gum, and targeted blockers, recovery isn’t just faster. It’s smoother, safer, and less painful in the long run.

Desmond Khoo

December 8, 2025 AT 04:58Louis Llaine

December 9, 2025 AT 07:40Jane Quitain

December 10, 2025 AT 13:18Sam Mathew Cheriyan

December 11, 2025 AT 19:41Ernie Blevins

December 13, 2025 AT 05:09David Brooks

December 13, 2025 AT 10:48Sadie Nastor

December 14, 2025 AT 09:49Kurt Russell

December 14, 2025 AT 21:16Stacy here

December 16, 2025 AT 02:00Kyle Flores

December 17, 2025 AT 15:32Ryan Sullivan

December 18, 2025 AT 04:28Olivia Hand

December 20, 2025 AT 02:51