When a hospital adds a new generic drug to its formulary, it’s not just a paperwork update. It’s a decision that affects thousands of patients, hundreds of staff, and millions of dollars in annual spending. Behind every generic medication on a hospital shelf is a rigorous, evidence-driven process designed to balance safety, effectiveness, and cost. This isn’t guesswork. It’s a structured system built over decades - and it’s changing how care is delivered today.

What Exactly Is a Hospital Formulary?

A hospital formulary is a living list of approved medications that clinicians can prescribe within the facility. Unlike retail pharmacies where patients can buy almost any brand or generic, hospitals operate on closed formularies. That means only the drugs on the approved list are routinely stocked and dispensed. If a doctor wants to order something off-formulary, they usually need to jump through hoops - like getting prior authorization or proving it’s medically necessary. This system started taking shape in the 1970s in the U.S., as hospitals realized they couldn’t afford to stock every version of every drug. With hundreds of drugs available for common conditions like high blood pressure or diabetes, standardization became essential. Today, most hospitals maintain between 300 and 1,000 drug dosage forms on their formulary. And the vast majority - about 90% - of prescriptions filled in hospitals are for generic drugs.How Do Hospitals Decide Which Generics to Include?

The process starts with the Pharmacy and Therapeutics (P&T) committee. This group isn’t made up of administrators or marketers. It’s typically 12 to 15 people: pharmacists with board certification in pharmacotherapy, physicians specializing in relevant fields, a healthcare economist, and sometimes a nurse or patient advocate. They meet monthly or quarterly to review new drug requests. When a manufacturer wants its generic drug added, they submit a dossier. This includes:- Clinical trial data showing safety and efficacy

- Pharmacokinetic studies proving bioequivalence to the brand-name drug

- Information on manufacturing quality and supply reliability

- Cost data - both acquisition price and projected impact on total care

- Adverse event rates from the FDA’s FAERS database

- Real-world outcomes from 15-20 published clinical studies

- Patient compliance data - for example, a once-daily generic pill might be preferred over one that needs to be taken three times a day

- Supply chain stability - a drug that’s been recalled or has shortages three times in a year gets flagged

Why Cost Isn’t the Only Factor - But It’s Still Huge

It’s easy to assume hospitals pick generics just because they’re cheaper. That’s part of it - but not the whole story. Generic drugs make up 90% of prescriptions in hospitals but only 26% of total drug spending. Why? Because the real savings come from avoiding complications. A 2022 Johns Hopkins study found switching to formulary-preferred generic anticoagulants saved $1.2 million in a single year - not because the pills cost less, but because patients had fewer bleeding events and shorter hospital stays. That’s why top hospitals now use “total cost of care” models. They don’t just look at the price per pill. They ask: Does this drug reduce readmissions? Lower ER visits? Cut down on lab tests or nursing interventions? One hospital in Minnesota found that choosing a cheaper generic diuretic led to more frequent electrolyte imbalances, which triggered more lab draws and nurse calls. The net cost went up. That’s where groups like the Institute for Clinical and Economic Review (ICER) come in. Their independent cost-effectiveness analyses are now used by 65% of large hospital systems. They help answer: Is this drug worth the money - not just in dollars, but in lives saved and quality of life improved?

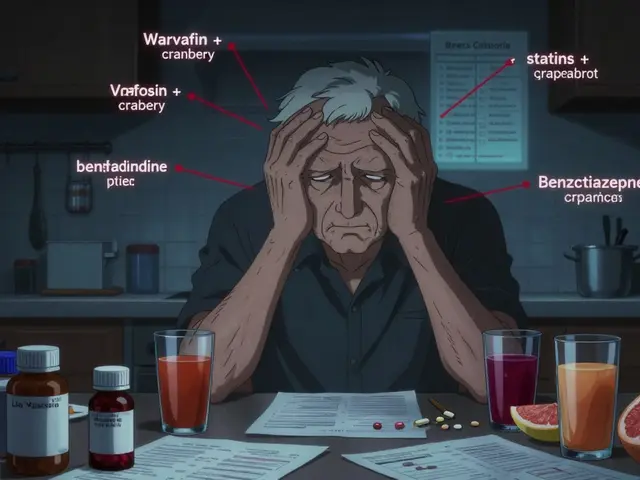

Tiers, Trade-Offs, and Therapeutic Interchange

Most hospital formularies are divided into three to five tiers. Generic drugs almost always sit in Tier 1 - the lowest cost-sharing tier for patients. But that doesn’t mean all generics are treated the same. For example, a hospital might have five different generic versions of lisinopril (an ACE inhibitor for high blood pressure). The formulary might only list two as preferred: one from a manufacturer with consistent supply and lower adverse event reports. The other three are non-preferred. A doctor can still prescribe them, but the pharmacist must contact the prescriber first - and often the patient has to pay more. This is called therapeutic interchange. Pharmacists are allowed to swap a non-preferred generic for a preferred one at the point of dispensing - as long as it’s clinically equivalent. But here’s where tension shows up. A 2022 American Pharmacists Association survey found 57% of pharmacists reported conflicts with physicians over these substitutions. Doctors sometimes feel they know what’s best for their patient. Pharmacists argue that if two drugs are bioequivalent, the safer, cheaper, more reliable one should be used - unless there’s a documented reason not to.Real-World Problems: Shortages, Errors, and Resistance

It’s not all smooth sailing. In 2022, ASHP tracked 268 generic drug shortages across the U.S. When a preferred generic runs out, hospitals scramble. Some temporarily remove it from the formulary. Others activate a pre-approved list of alternatives. At Mayo Clinic, they created “therapeutic alternatives committees” that proactively map out backup options for high-risk drugs. They’ve maintained continuity of care in 98% of shortage cases. But even when the system works, people notice the change. Nurses report confusion when a familiar pill changes shape or color. A 2023 AllNurses.com thread with 142 comments showed 73% of nurses saw temporary medication errors during formulary switches. One nurse wrote: “I gave a patient the wrong generic because I thought it was the same pill - different manufacturer, different imprint.” Physicians, too, feel constrained. A 2021 AMA survey found 32% said formulary restrictions had directly affected patient care - like delaying treatment for a rare condition because the only effective drug wasn’t on the list.

The Future: Personalization, Equity, and Regulation

The next wave of change is already here. Some academic hospitals are starting to use pharmacogenomic data - genetic testing results - to guide formulary choices. For example, if a patient has a gene variant that makes them metabolize a drug slowly, the formulary might prioritize a different generic version that’s less likely to cause side effects. The 2022 Inflation Reduction Act will also reshape formularies. By 2025, Medicare Part D rules will require hospitals to align their drug lists with new price caps and rebate structures. That means formulary decisions will increasingly reflect federal policy, not just local needs. And equity is becoming a formal criterion. ASHP’s 2023 update now requires formulary committees to ask: Does this drug choice create barriers for low-income patients? For non-English speakers? For those without reliable transportation to refill prescriptions?What’s Next for Hospitals?

By 2028, the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality predicts all Medicare-certified hospitals will be required to have formal, evidence-based formularies. That’s not a distant idea - it’s already happening in 98% of hospitals with over 100 beds. The key isn’t just picking the cheapest drug. It’s picking the right drug - the one that works best for the population, with the least risk, and the lowest total cost. That’s the goal. And it’s why hospital formularies aren’t just administrative tools. They’re clinical decision engines - quietly shaping the quality of care every day.How often do hospital formularies get updated?

Most academic medical centers review their formularies quarterly. Community hospitals typically do it twice a year. Urgent requests - like adding a new generic during a drug shortage - can be processed in as little as 14 to 21 days. Routine reviews take 45 to 60 days to complete.

Can a hospital use a generic drug that’s not FDA-approved?

No. Every generic drug on a hospital formulary must be FDA-approved and listed in the Orange Book with an AB therapeutic equivalence rating. Hospitals do not stock or prescribe unapproved generics - even if they’re cheaper or available overseas. Safety and legal compliance come first.

Why do some generic drugs cost more than others, even if they’re the same medicine?

Manufacturing quality, supply chain reliability, and packaging can all affect price. A generic made by a company with consistent quality control and fewer recalls may cost more per pill - but save money overall by reducing adverse events and hospital readmissions. Hospitals choose based on total cost of care, not just the sticker price.

Do formularies affect patient outcomes?

Yes. Studies show hospitals with strong, evidence-based formularies have lower medication errors, fewer adverse drug events, and reduced readmission rates. For example, a 2023 study in the Journal of Managed Care & Pharmacy found that hospitals following ASHP guidelines had 18-22% lower medication costs without any drop in clinical outcomes.

Are biosimilars included in hospital formularies the same way as generics?

Not yet. Biosimilars are more complex than traditional generics. While generics are chemically identical to their brand-name counterparts, biosimilars are highly similar - but not identical - to biologic drugs. Only 37% of hospital formularies have formal protocols for evaluating biosimilars as of 2023. Their inclusion requires additional clinical data, and many hospitals are still developing policies for substitution.

Napoleon Huere

January 25, 2026 AT 11:18It's wild to think that behind every pill on a hospital shelf is a committee of people arguing over bioequivalence and supply chain logistics like it's a damn chess match. We treat drugs like commodities, but they're not-they're extensions of human biology. And yet, we let spreadsheets decide who gets which version of a drug that might keep them alive. The real question isn't how they pick generics-it's why we let cost be the silent god of care.

James Nicoll

January 26, 2026 AT 02:52So let me get this straight-we have a system so complex it needs a PhD in pharmacoeconomics just to prescribe a blood pressure pill, and yet we still have nurses giving out the wrong generic because the pill looks different? 🤡

At this point, I’m just waiting for the hospital to start requiring patients to pass a drug ID quiz before they get their meds.

Uche Okoro

January 27, 2026 AT 11:11The structural inefficiencies inherent in the current formulary paradigm are exacerbated by the epistemological dissonance between pharmacokinetic equivalence and clinical outcomes. While AB-rating ensures bioequivalence at the molecular level, it fails to account for inter-individual pharmacodynamic variance, particularly in polypharmacy cohorts. The reliance on FAERS and retrospective cohort studies introduces significant confounding bias, rendering many formulary decisions statistically underpowered. Furthermore, the commodification of therapeutic interchange as a cost-containment strategy neglects the ontological primacy of patient autonomy in medication selection.

Ashley Porter

January 28, 2026 AT 08:50I’ve seen this play out in real time. A patient on lisinopril for 8 years gets switched to a different generic because the hospital got a better bulk deal. No one told her. She showed up with dizziness, thought she was having a stroke. Turned out the new one had a different filler-she was allergic. Took three days to figure it out. The system’s efficient until it’s not. And then it’s a nightmare.

shivam utkresth

January 28, 2026 AT 10:51Man, this whole thing is like trying to pick the best chai from 20 different brands-same ingredients, different spice ratios, and someone’s grandma swears by one. Hospitals are doing the right thing trying to standardize, but they forget that people aren’t data points. A pill that saves money but makes someone feel like crap? That’s not a win. It’s a quiet tragedy wrapped in a formulary PDF.

Also, biosimilars are the wild west right now. We need way more clarity before we start swapping them like candy.

John Wippler

January 28, 2026 AT 18:33Let’s not pretend this is just about money. This is about dignity. When a nurse has to explain to a 72-year-old why their heart pill now looks like a tiny blue rock instead of a white oval, and they panic because ‘it’s not the same,’ that’s not a cost-saving win-that’s a failure of communication.

But here’s the good news: we’re getting better. Formularies are starting to include equity checks, patient feedback loops, even pharmacogenomics. This isn’t bureaucracy-it’s evolution. And it’s slow, messy, and necessary. We’re not just choosing pills-we’re choosing how we care for people. And that? That’s worth fighting for.

Kipper Pickens

January 30, 2026 AT 16:54The FDA’s AB-rating is the baseline, not the ceiling. What’s fascinating is how hospital P&T committees have become de facto clinical arbiters-bypassing even the FDA’s post-market surveillance in some cases by layering on real-world evidence. The real innovation isn’t in the drugs, it’s in the data infrastructure. Hospitals are now aggregating EHR data, pharmacy logs, and even patient-reported outcomes to feed into their decisions. That’s next-gen formulary science. The challenge? Making sure the data doesn’t become a black box. We need transparency, not just optimization.

Aurelie L.

January 30, 2026 AT 18:07So… you’re telling me a nurse gave someone the wrong pill because it looked different? And this is normal? 🤦♀️

I need a drink.

Joanna Domżalska

January 31, 2026 AT 20:23Generic drugs aren’t cheaper-they’re just worse. Why do hospitals think people are okay with pills that don’t work the same? Because they’re cheaper? That’s not medicine, that’s rationing with a PowerPoint.

And don’t even get me started on ‘total cost of care.’ That’s just corporate speak for ‘we don’t care if you get sick again.’

Faisal Mohamed

February 2, 2026 AT 13:20Bro, formularies are basically the hospital’s Spotify algorithm for meds 🎧

‘You liked lisinopril? Try this other generic-it’s similar, cheaper, and made by a company that didn’t get sued last year.’

But then you get the weird one that gives you weird dreams and now you’re side-eyeing your blood pressure pill like it’s a bad ex.

Also biosimilars are the TikTok of pharma-everyone’s talking about them but no one really knows how they work 😅

Josh josh

February 2, 2026 AT 14:07so like the hospital picks the cheapest pill and then everyone gets confused because it looks different and someone gets the wrong one and its all just a mess

why cant we just let doctors pick what they want

bella nash

February 3, 2026 AT 17:05It is imperative to underscore the methodological rigor inherent in the institutional formulary selection process, which operates under a framework of evidence-based pharmacotherapy, guided by peer-reviewed clinical literature, regulatory compliance, and fiscal stewardship. The conflation of cost-efficiency with clinical compromise is both empirically unfounded and epistemologically reductive. The system, while imperfect, is intentionally designed to mitigate therapeutic heterogeneity and optimize population-level outcomes.

Sally Dalton

February 4, 2026 AT 17:45I just want to say thank you to every pharmacist who has to deal with this mess. Seriously. You’re the unsung heroes who catch the wrong generic before it gets to the patient, who explain why the pill changed color, who fight with doctors to keep things safe. I’ve seen you cry in the break room after a 12-hour shift because someone yelled at you for not giving them the ‘old’ pill. You’re doing God’s work. 🤍

Curtis Younker

February 5, 2026 AT 16:21This is the most important thing no one talks about. Hospitals aren’t just saving money-they’re saving lives. When you cut down on medication errors, you cut down on ER visits. When you pick a generic that’s easier to take once a day, people actually take it. When you avoid a drug that causes kidney damage in seniors, you keep people out of the hospital. It’s not sexy, it’s not viral, but this is how real healthcare works. It’s boring, it’s detailed, it’s full of spreadsheets and committees and nerds in lab coats arguing over bioequivalence percentages. And guess what? That’s what keeps you alive when you’re 75 and on five meds. So yeah, let the committees do their job. They’re not the enemy. They’re the quiet guardians of your next birthday.

Shawn Raja

February 7, 2026 AT 12:06So we’ve turned medicine into a corporate supply chain game where the only metric that matters is ‘lowest cost per pill’-but then we get mad when someone has a bad reaction because the new generic has a different dye?

Meanwhile, the same hospitals charge $2000 for a 10-minute visit.

It’s not a system. It’s a farce. And the worst part? Everyone knows it. We’re just too tired to fix it.

Also, biosimilars are coming. And they’re gonna break this whole thing open. Buckle up.