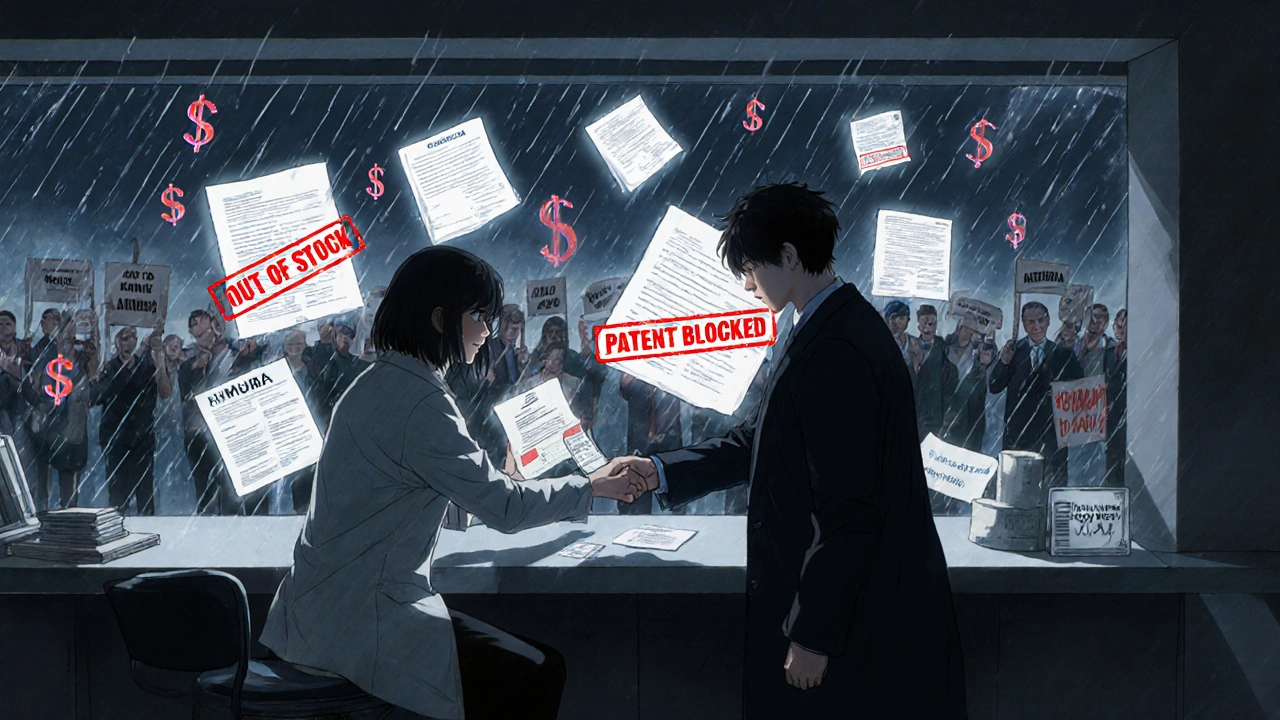

When a blockbuster drug’s patent runs out, the price should drop-fast. Generic versions flood the market, competition kicks in, and patients pay a fraction of what they used to. But in many cases, that doesn’t happen. Not because generics are slow to arrive, but because the original brand has already moved the goalposts. This is evergreening: a legal but controversial strategy used by pharmaceutical companies to delay generic competition and keep prices high, sometimes for decades beyond the original patent’s expiration.

What Evergreening Really Means

Evergreening isn’t about inventing new medicines. It’s about tweaking old ones. A company takes a drug that’s about to lose patent protection-say, a pill for acid reflux or an insulin formulation-and makes a small change: a new coating, a slightly different dose, a once-daily capsule instead of two pills a day, or a combo with another inactive ingredient. Then they file a new patent on that tweak. Suddenly, the clock resets. Generic makers can’t enter the market until that new patent expires, even if the active ingredient hasn’t changed. This isn’t a loophole. It’s a system built into U.S. drug law. The 1984 Hatch-Waxman Act was meant to balance innovation with access. It gave brand-name companies 20 years of patent protection and up to five years of exclusivity for new drugs. But it also created a fast-track for generics. What happened next? Companies realized they could game the system. Instead of investing billions in new molecules, they invested a few million in minor reformulations-and kept their profits rolling.How It Works: The Tactics Behind the Strategy

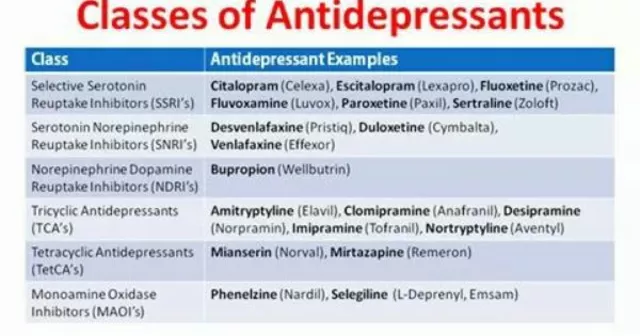

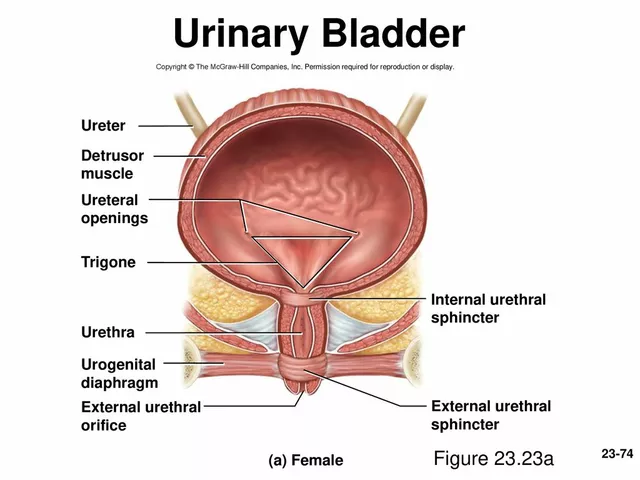

There’s no single way to evergreen a drug. There are dozens. Here are the most common ones:- Product hopping: A company replaces the original drug with a new version-often a pill that dissolves in the mouth, or an inhaler instead of a tablet-and then stops making the old version. Patients and doctors are pushed toward the new one, even if it offers no real clinical benefit. AstraZeneca did this with Prilosec (omeprazole) and Nexium (esomeprazole). Nexium was just the left-handed version of the same molecule. It cost more. It didn’t work better. But because it had a new patent, generics couldn’t touch it for years.

- Patent thickets: One drug, hundreds of patents. AbbVie’s Humira, a biologic used for rheumatoid arthritis and Crohn’s disease, has over 247 patents filed around it. Each one covers a slightly different use, dosage, delivery method, or manufacturing process. Generic makers don’t just need to prove their version is safe-they need to navigate a maze of legal claims just to get to court. Many give up before they start.

- Authorized generics: The brand company licenses its own drug to a generic manufacturer. The generic hits the market, but it’s sold under the same brand name. It’s still expensive. It’s still controlled by the original company. And it keeps other generics out by occupying shelf space and pharmacy formularies.

- Orphan drug extensions: A drug approved for a rare disease gets seven years of exclusivity. Some companies take a common drug and rebrand it for a tiny patient group-say, one in 10,000 people-to lock in extra years of protection.

- Pediatric exclusivity: If a company runs new clinical trials on children, they get six extra months of exclusivity. Sometimes, these trials are done on drugs that have no real pediatric use. But the extension still counts.

Why It’s So Profitable

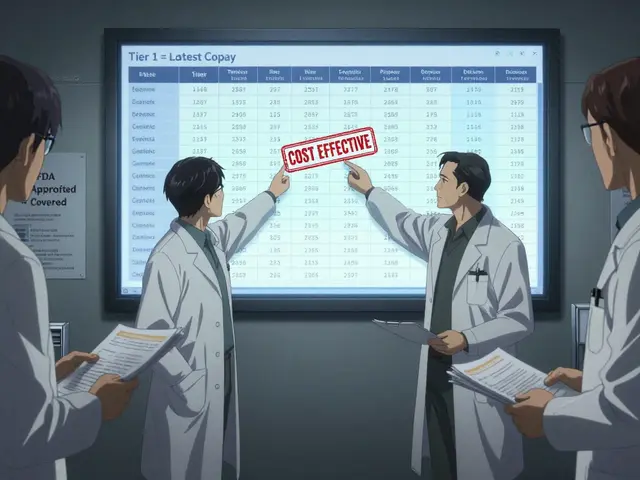

Developing a brand-new drug costs about $2.6 billion and takes 10 to 15 years. Evergreening? A fraction of that. A new formulation might cost $50 million to develop and take two years. The payoff? Decades of monopoly pricing. Take Humira. In 2023, it was still the top-selling drug in the world, bringing in over $40 million per day. That’s because AbbVie kept delaying generics through patent stacking. Even after the core patent expired, other patents kept generics away until 2023-nearly 20 years after launch. That’s not innovation. That’s financial engineering. AstraZeneca did the same with drugs for diabetes and GERD. Their six key drugs accumulated over 90 extra years of patent protection through evergreening. That’s not a mistake. That’s the business model.

The Human Cost

When generics enter the market, prices drop by 80 to 85% within the first year. That’s the power of competition. But evergreening blocks that. Patients pay more. Insurance companies pay more. Medicare pays more. And when people can’t afford their meds, they skip doses, delay refills, or stop taking them altogether. Diabetes, heart disease, autoimmune disorders-these aren’t rare conditions. They affect millions. When a drug like Nexium or Humira stays expensive because of evergreening, it doesn’t just hurt individuals. It strains entire healthcare systems. In Australia, where drug prices are regulated, patients still feel the ripple effects: when U.S. prices stay high, global supply chains follow suit. In low-income countries, the impact is even worse. The WHO has called evergreening a direct barrier to medicine access.Who’s Fighting Back?

Regulators and lawmakers are starting to push back. In 2022, the U.S. Federal Trade Commission sued AbbVie over Humira’s patent strategy, calling it an illegal monopoly. The case is ongoing. The Inflation Reduction Act of 2022 gave Medicare the power to negotiate prices for the 10 most expensive drugs-some of which are protected by evergreening. That alone could reduce the financial incentive to extend patents. The European Medicines Agency now requires companies to prove a new formulation offers “significant clinical benefit” before granting extra exclusivity. That’s a big shift. In the U.S., the Patent and Trademark Office has started rejecting obvious patent applications-like changing a pill’s color or shape without any functional improvement. But the system is still tilted. Companies spend millions on lobbyists. They hire top patent lawyers. They file lawsuits against generic makers just to delay them-even if the patent is weak. And they win more often than not.

What’s Next?

The next wave of evergreening is even more complex. Companies are now patenting:- Nanotechnology versions of old drugs

- Genetic tests that predict who responds to a drug

- Biologic versions of small-molecule drugs

- Data exclusivity tricks that block generics from using clinical trial data

Is There a Better Way?

Yes. The system could reward real innovation-not legal loopholes. Imagine if companies got a cash prize for developing a truly new drug. Or if patent extensions required proof of measurable patient benefit-not just a new capsule. Or if the FDA could fast-track generics unless the brand proved the new version was significantly better. Right now, the system rewards delay. It rewards complexity. It rewards lawyers over lab coats. The truth? Most patients don’t care if a pill is coated in blue or red. They care if they can afford it. And when evergreening keeps prices high, it’s not just a business tactic-it’s a public health issue.Is evergreening illegal?

No, evergreening isn’t illegal in most cases-it’s legal under current patent law. But it’s often seen as abusive. Courts and regulators are increasingly challenging patents that cover minor changes without real therapeutic benefits. The FTC’s lawsuit against AbbVie over Humira is one example of legal action against these practices. While not outright banned, many of these tactics are under growing scrutiny.

How do generics finally get approved if a drug is evergreened?

Generics can only enter the market after all patents covering the drug expire-or if they successfully challenge the patents in court. Many generic companies avoid filing lawsuits because the legal costs can run into tens of millions of dollars. Some wait until the last patent falls. Others partner with investors or nonprofits to fund litigation. In rare cases, the FDA may grant a waiver if the brand company isn’t marketing the drug or if the patent is clearly invalid.

Does evergreening improve patient outcomes?

Almost never. Studies show that most evergreened versions-like Nexium or extended-release capsules-offer no meaningful clinical advantage over the original. In some cases, they’re even less effective. The goal isn’t better health. It’s longer profits. When patients are switched to a new version just to avoid generics, it often leads to confusion, higher costs, and no better results.

Are there any drugs that haven’t been evergreened?

Yes-but they’re becoming rarer. Older drugs like aspirin, metformin, and penicillin are too generic to evergreen. But almost every blockbuster drug from the last 30 years-especially those making over $1 billion a year-has been subject to some form of evergreening. If a drug is profitable, companies will try to extend its life. The trend is clear: the bigger the drug, the more patents it accumulates.

What can patients do about evergreening?

Patient advocacy matters. Ask your doctor if a generic version is available. If your prescription is expensive, ask if there’s an older, off-patent alternative. Join patient groups that lobby for drug pricing reform. Support legislation that limits patent extensions without clinical benefit. And don’t assume a newer version is better-ask for the evidence. Your voice helps pressure regulators and lawmakers to fix the system.

Yash Hemrajani

November 29, 2025 AT 22:55So let me get this straight - we’re paying $1000 for a pill that’s chemically identical to a $2 generic, just because Big Pharma figured out how to patent the color of the coating? Brilliant. Absolute genius. I’d invest in a company that patents the air you breathe if I thought they could get away with it.

Jermaine Jordan

November 30, 2025 AT 08:38This is not just a failure of regulation - it is a moral catastrophe disguised as capitalism. We are living in a world where human health is held hostage by legal loopholes written by lobbyists with PhDs in corporate law. The fact that Humira generated $40 million per day while patients skipped doses to afford rent? That’s not capitalism. That’s extortion with a white coat.

Chetan Chauhan

December 1, 2025 AT 13:50Pranab Daulagupu

December 2, 2025 AT 12:26Patent thickets = regulatory capture in action. The system incentivizes litigation over innovation. We’ve created a feedback loop where legal strategy outpaces therapeutic progress. This isn’t market efficiency - it’s rent-seeking at scale.

Sean Slevin

December 3, 2025 AT 10:53Chris Taylor

December 5, 2025 AT 09:10I had to choose between my insulin and my rent last year. I took the rent. I’m still alive. But I’m not okay. This isn’t about patents - it’s about people being treated like balance sheets.

Melissa Michaels

December 6, 2025 AT 16:38While the legal mechanisms enabling evergreening are technically permissible under current statutory frameworks, the ethical implications are profound and demand immediate policy intervention. The disconnect between public health outcomes and corporate profit incentives is no longer tenable.

Nathan Brown

December 8, 2025 AT 09:17It’s not just about drugs - it’s about what we value as a society. Do we reward creativity? Or do we reward the cleverness of people who find ways to turn suffering into a spreadsheet? I keep asking myself: if we can land on Mars, why can’t we make medicine affordable? Maybe the answer is simpler than we think - we just don’t care enough.

Matthew Stanford

December 8, 2025 AT 20:12Let’s not villainize the companies - they’re just playing the game we designed. The real question is: who designed the rules? And why did we let them? Maybe it’s time we rewrite the playbook - not with anger, but with collective will.

Olivia Currie

December 10, 2025 AT 11:37Imagine if every time a company extended a patent, they had to donate 10% of the profits to a global health fund. Suddenly, the ‘tweak’ isn’t just a cash grab - it’s a contribution. We could end global medicine shortages in a decade. But no - we’d rather let CEOs buy yachts. 😤

Curtis Ryan

December 12, 2025 AT 04:13Rajiv Vyas

December 12, 2025 AT 10:31Evergreening? Nah. This is just the Illuminati’s way of keeping us docile. The real drug is in the water. The patents? A distraction. They don’t want you healthy - they want you dependent. Check the FDA’s funding sources. You’ll see the same names over and over. Coincidence? I think not.

farhiya jama

December 12, 2025 AT 19:01Ugh. I read this whole thing and now I’m just tired. Can we talk about something that doesn’t make me want to cry into my $200 bottle of ibuprofen?

Ifeoma Ezeokoli

December 14, 2025 AT 08:27Back home in Nigeria, my cousin died because her epilepsy meds were too expensive. No one here talks about this like it’s a crime - but it is. We don’t need more patents. We need more humanity. The world is bigger than the U.S. patent office.