Drug Toxicity: Signs, Risks, and How to Stay Safe

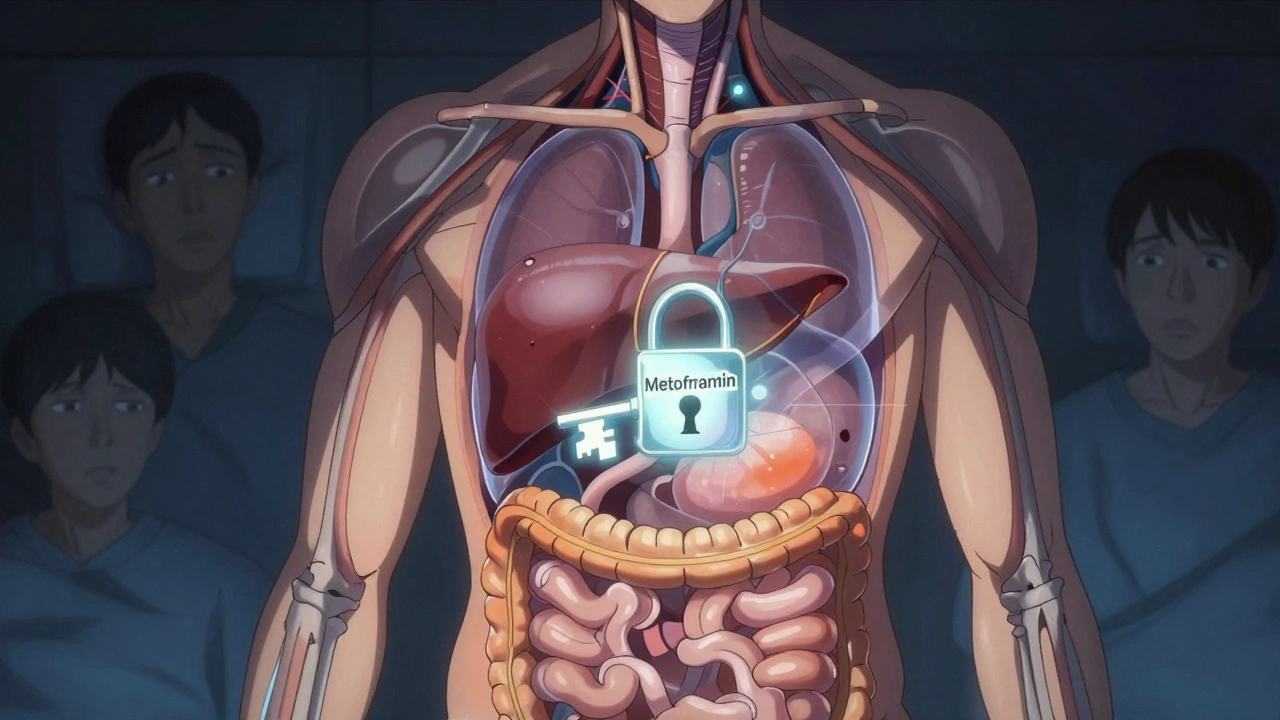

When your body can’t process a medication properly, drug toxicity, the harmful buildup of a drug or its byproducts in the body can occur—even at normal doses. It’s not always about taking too much. Sometimes, it’s what you take it with. A common antibiotic like clarithromycin can push statin levels into dangerous territory, triggering muscle damage. Or a simple painkiller, taken daily for years, might quietly harm your kidneys or liver. Drug toxicity doesn’t always scream for attention. It often whispers—through fatigue, nausea, skin changes, or unexplained muscle pain—and by the time it’s noticed, it’s already caused real harm.

This is why drug interactions, when two or more substances affect each other’s behavior in the body matter so much. Caffeine can mess with thyroid meds. Grapefruit juice can turn a heart pill into a poison. Even something as harmless as a supplement, a substance taken to support health, often without medical oversight like St. John’s wort can cancel out birth control or trigger serotonin overload. The FDA’s flush list exists because some drugs—like fentanyl patches—are deadly if a child finds them in the trash. Toxicity isn’t just about overdose. It’s about hidden risks, delayed reactions, and the quiet erosion of health from long-term use.

And it’s not just the drugs themselves. Your age, your liver function, your other conditions—all of it changes how your body handles medication. Older adults are more vulnerable. People with kidney disease can’t clear toxins the way they used to. That’s why uremic symptoms like itching and nausea aren’t just discomfort—they’re red flags that toxins are piling up. The same goes for steroid-induced high blood sugar or PPIs slowly weakening your bones over time. Drug toxicity isn’t a one-time event. It’s a pattern. And the more you know about how your meds work together, the better you can stop it before it starts.

What you’ll find below isn’t theory. It’s real stories from people who’ve been there: the mom who saved her kid by learning the flush list, the man who avoided muscle damage after switching antibiotics, the woman who tracked her pills and caught an overdose before it happened. These aren’t edge cases. They’re everyday situations that turn dangerous without awareness. You don’t need a medical degree to protect yourself. You just need to know what to look for—and what to ask.