PPI Fracture Risk Assessment

Personal Information

PPI Usage

Additional Risk Factors

Risk Assessment

Enter your information above to see your fracture risk assessment

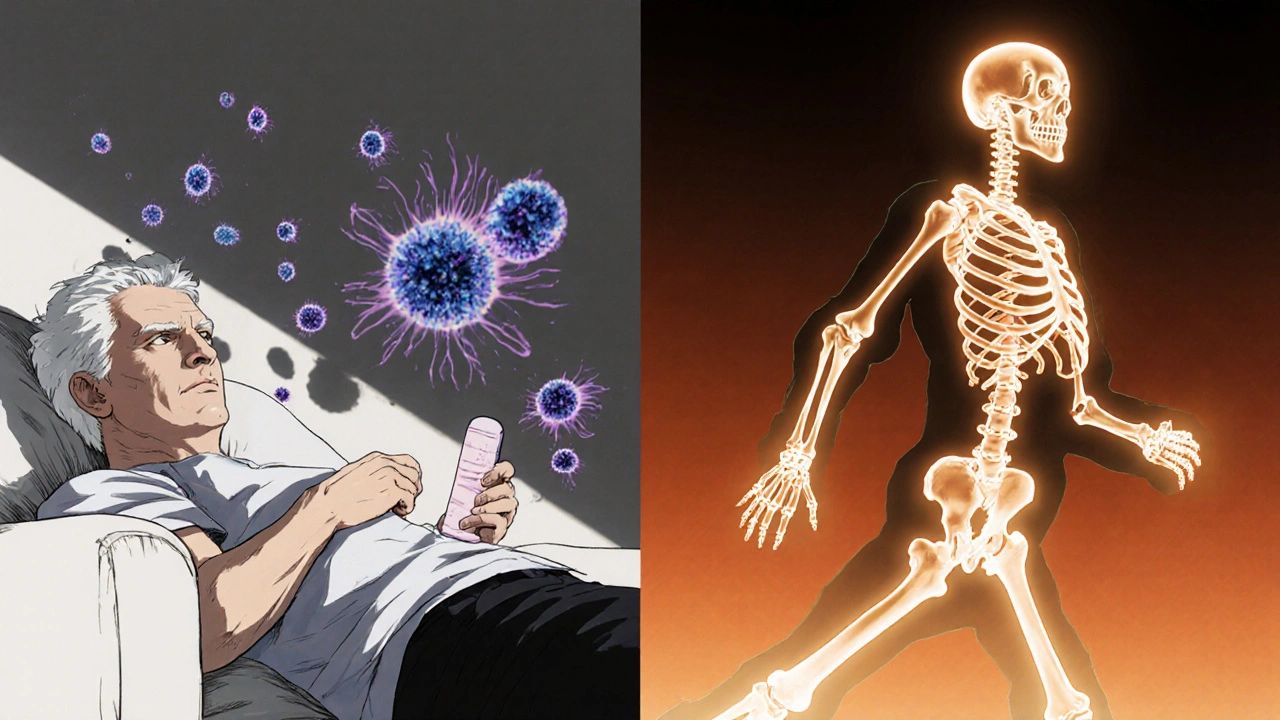

If you’ve been taking a proton pump inhibitor (PPI) like omeprazole or pantoprazole for heartburn or acid reflux, you might have heard rumors about bone fractures. It’s not just a scare tactic-it’s a real, studied concern. The FDA flagged it back in 2010, and since then, dozens of large studies have tried to untangle whether these common stomach meds are quietly weakening your bones. The truth? It’s complicated. For most people, the risk is small. But for some, especially older adults or those on long-term, high-dose PPIs, the numbers add up in a way that can’t be ignored.

How PPIs Work-and Why That Might Hurt Your Bones

Proton pump inhibitors block the acid-producing pumps in your stomach lining. That’s why they’re so effective for GERD, ulcers, and other acid-related conditions. But your stomach acid isn’t just there to digest food-it’s also critical for absorbing calcium, magnesium, and other minerals your bones need to stay strong.

Most calcium supplements, like calcium carbonate, need acid to dissolve properly. If your stomach acid is suppressed for months or years, your body may not absorb enough calcium to keep up with bone remodeling. Over time, that can lead to lower bone density. It’s not that PPIs directly destroy bone-they just make it harder for your body to rebuild it.

There’s also a second, less obvious pathway: long-term PPI use raises levels of gastrin, a hormone that stimulates acid production. Higher gastrin might trigger changes in bone cells, increasing activity in cells that break down bone (osteoclasts) and slowing down those that build it (osteoblasts). One 2022 review in PMC called this a "double hit"-less calcium absorption plus altered bone cell behavior.

The Evidence: How Big Is the Risk?

The data doesn’t show a dramatic spike in fractures, but it does show a consistent, measurable increase in certain groups.

- A 2019 meta-analysis in the Journal of Bone and Mineral Research found that people on long-term PPIs had a 20-30% higher risk of hip, wrist, and spine fractures.

- The Manitoba study tracked over 10,000 people and found those on PPIs for seven or more years had more than four times the risk of hip fracture compared to non-users.

- A 2020 study comparing PPI users to H2 blockers (like ranitidine) found PPI users had a 27% higher risk of hip fracture.

- For postmenopausal women, one 2019 study in the American Journal of Gastroenterology reported a 35% higher risk of hip fracture with long-term PPI use.

It’s not just about how long you take it-it’s also about dose. People taking high-dose PPIs (like 2 or more pills daily) had up to a 67% higher fracture risk compared to those on low doses.

But here’s the catch: these are observational studies. That means they show a link, but they can’t prove PPIs are the direct cause. People on long-term PPIs often have other health problems-like chronic kidney disease, diabetes, or a history of falls-that also raise fracture risk. Some researchers, like Dr. Leslie Targownik, argue these factors might explain most of the association.

PPIs vs. H2 Blockers: Which Is Safer for Your Bones?

Not all acid-reducing drugs are the same. H2 blockers like famotidine or ranitidine work differently-they don’t shut down acid production as completely as PPIs. And they appear to carry less bone risk.

One large 2020 study compared over 50,000 PPI users to 50,000 H2 blocker users over age 50. The PPI group had a 27% higher risk of hip fracture. Another study in children found no overall fracture risk with PPIs, but a 22% higher risk of lower-limb fractures in kids aged 6-12, suggesting the bone impact might be age-dependent.

The FDA’s 2010 review looked at seven studies. Six showed a link between PPIs and fractures. One didn’t. The difference? The study that found no link excluded people with other fracture risk factors. That tells us something important: PPIs might not be dangerous by themselves-but they can be risky when combined with other problems.

Who’s Most at Risk?

Not everyone needs to worry. The risk is concentrated in specific groups:

- People over 65-bone density naturally declines with age.

- Postmenopausal women-lower estrogen means faster bone loss.

- Those with low body weight (under 57 kg or 125 lbs)-less bone mass to begin with.

- People who’ve had a prior fracture-one fracture is a strong predictor of another.

- Those on corticosteroids (like prednisone)-these drugs directly weaken bone.

- Long-term users-especially those on high doses for more than a year.

If you fall into one or more of these categories and have been on PPIs for over 8 weeks, it’s worth talking to your doctor about your bone health.

What Should You Do If You’re on PPIs Long-Term?

Don’t stop your medication cold turkey. Sudden withdrawal can cause rebound acid reflux that’s worse than before. Instead, take these steps:

- Ask if you still need it. Up to 70% of long-term PPI prescriptions are unnecessary. Ask your doctor: "Is this still helping me? Can I try to taper off?"

- Use the lowest effective dose. Many people take 20mg daily when 10mg would work. Some can even switch to every-other-day dosing.

- Switch to calcium citrate. Unlike calcium carbonate, calcium citrate doesn’t need stomach acid to absorb. Take 1,200 mg daily with vitamin D (800-1,000 IU).

- Get a bone density test. If you’re over 65, female, or have other risk factors, ask for a DEXA scan. It’s quick, painless, and covered by most insurance.

- Move more. Weight-bearing exercise like walking, dancing, or resistance training helps maintain bone strength.

- Limit alcohol and quit smoking. Both accelerate bone loss.

The American Geriatrics Society’s Beers Criteria even lists long-term, high-dose PPIs as potentially inappropriate for older adults unless there’s a clear, ongoing need.

The Bigger Picture: Benefits vs. Risks

PPIs save lives. They prevent bleeding ulcers, reduce the risk of esophageal cancer in people with severe GERD, and help people with chronic acid reflux live without pain. For someone with a history of GI bleeding or Barrett’s esophagus, the benefits of PPIs far outweigh the small increase in fracture risk.

The problem isn’t PPIs themselves-it’s how often they’re prescribed. Many people take them for mild heartburn that could be managed with diet changes, weight loss, or H2 blockers. Others stay on them for years after their original condition has resolved.

The American Gastroenterological Association says it best: "The absolute risk increase is small, and must be weighed against the proven benefits of appropriate PPI therapy."

What’s Next? New Research Coming in 2025

Scientists are still working to get clearer answers. The NIH-funded PPI-BONE study, tracking 15,000 people over five years, is due to release final results in mid-2025. This study is designed to control for confounding factors like diet, activity, and other medications-something earlier studies couldn’t do well.

Meanwhile, the American College of Gastroenterology is updating its prescribing guidelines, expected in early 2024. These will likely push doctors to be more cautious about long-term use and emphasize regular re-evaluation.

For now, the message is simple: don’t panic, but don’t ignore it. If you’ve been on a PPI for more than a year, especially if you’re over 65 or have other risk factors, it’s time to have a conversation with your doctor. Your bones will thank you.

Do proton pump inhibitors cause osteoporosis?

PPIs don’t directly cause osteoporosis, but long-term use-especially at high doses-may contribute to lower bone density and increase fracture risk. This happens mainly because reduced stomach acid can interfere with calcium absorption, and some evidence suggests changes in bone cell activity. The risk is small for most people but becomes more significant in older adults, postmenopausal women, and those with other bone health risk factors.

Can I take calcium supplements while on PPIs?

Yes, but choose calcium citrate, not calcium carbonate. Calcium citrate doesn’t require stomach acid to be absorbed, so it works better when your acid levels are low. Take 1,200 mg daily along with 800-1,000 IU of vitamin D. Spread your doses throughout the day for better absorption.

Are H2 blockers safer for bones than PPIs?

Yes, studies suggest H2 blockers like famotidine or ranitidine carry a lower risk of fractures compared to PPIs. They reduce acid less completely, so calcium absorption isn’t as affected. If you’re on long-term acid suppression and concerned about bone health, ask your doctor if switching to an H2 blocker is a reasonable option.

How long is too long to be on a PPI?

Most guidelines recommend limiting PPI use to 4-8 weeks unless there’s a clear medical need. If you’ve been on them for more than a year, it’s time to re-evaluate. Many people stay on PPIs longer than necessary because symptoms return when they stop-this is called rebound acid hypersecretion, not a true relapse. With proper tapering and lifestyle changes, many can reduce or stop PPIs safely.

Should I get a bone density test if I’m on PPIs?

If you’re over 65, a postmenopausal woman, have a history of fractures, low body weight, or take corticosteroids, yes. The Endocrine Society recommends a DEXA scan for anyone on long-term PPI therapy (more than 8 weeks) with additional fracture risk factors. It’s a simple, non-invasive test that can guide whether you need extra bone protection.

Michael Salmon

November 19, 2025 AT 01:48Let me guess - you’re one of those people who thinks every drug is a poison unless it’s prescribed by your yoga instructor. PPIs cause fractures? Sure. And sunlight causes skin cancer. Wake up. The absolute risk increase is less than 1% for most people. Meanwhile, people who stop PPIs cold turkey end up in the ER with bleeding ulcers. Don’t be a fearmonger. This isn’t a public service announcement for TikTok moms.

Joe Durham

November 20, 2025 AT 03:28I appreciate how balanced this post is. It doesn’t scare people, it informs them. I’ve been on omeprazole for 3 years for Barrett’s, and I didn’t know about the calcium citrate tip. I switched last month - no more stomach issues, and my doctor says my bone density is stable. Small changes, big impact. Thanks for the clarity.

Derron Vanderpoel

November 20, 2025 AT 15:24OMG I JUST REALIZED I’VE BEEN TAKING CALCIUM CARBONATE FOR 5 YEARS WHILE ON PPIs 😭 I’M SO STUPID. I’M GOING TO SWITCH TO CITRATE TOMORROW. I JUST GOT MY DEXA SCAN NEXT WEEK TOO. HOPE I DIDN’T DESTROY MY BONES. ALSO I THINK I’M ADDICTED TO PPIs bc I panic if I miss a dose. HELP. 🥲

Timothy Reed

November 21, 2025 AT 16:53It is essential to recognize that while observational data suggest an association between long-term PPI use and increased fracture risk, causality remains unproven. Confounding variables - including age, comorbidities, polypharmacy, and lifestyle factors - may significantly influence outcomes. Clinical decision-making must therefore be individualized, weighing documented benefits against potential risks. Regular reassessment of therapy duration is a cornerstone of prudent prescribing.

James Ó Nuanáin

November 23, 2025 AT 06:23As a British physician with 27 years’ experience, I must say: Americans have a pathological fear of acid. You treat heartburn like it’s a terrorist threat. In the NHS, we prescribe PPIs for two weeks, then ask if the patient still feels like a volcano. Most don’t. Yet here you are, on PPIs for 12 years because you ‘like your pizza’. This isn’t medicine - it’s consumerism disguised as healthcare. And now you’re blaming the drug for your own poor choices? Pathetic.

Nick Lesieur

November 23, 2025 AT 09:44So let me get this straight - you’re telling me I should stop taking my $10/month pill that lets me eat tacos without crying… and start eating kale and doing yoga instead? Cool. And how many of you guys have actually had a real ulcer? No? Then shut up. My stomach’s not a philosophy seminar.

Angela Gutschwager

November 24, 2025 AT 10:57Calcium citrate. Not carbonate. DEXA scan if over 65. Taper. Not quit. Done. 😌

Ellen Calnan

November 25, 2025 AT 20:56It’s funny how we treat medicine like a switch - on or off. But the body’s not a lightbulb. PPIs are a tool, not a trap. I used to think my acid reflux was ‘just stress’ until I collapsed from a bleeding ulcer at 42. Now I’m on low-dose PPI and I’m alive. But I also walk 6 miles a day, take my citrate, and avoid spicy food after 8 PM. It’s not the drug. It’s the lifestyle. And maybe… we’re just too lazy to change the rest.

Richard Risemberg

November 26, 2025 AT 06:52Man, I love how this post doesn’t just dump data - it gives you a roadmap. Like, ‘Hey, here’s the science, here’s the nuance, and here’s how to actually survive it.’ I’ve seen so many patients panic and quit PPIs, then come back with worse reflux and a new anxiety disorder. The real villain isn’t the pill - it’s the silence around how to use it wisely. This? This is the kind of content that saves lives without screaming. Kudos.

Andrew Baggley

November 26, 2025 AT 11:52You got this. Seriously. Switching to citrate, getting that scan, walking more - these aren’t punishments, they’re upgrades. Your bones don’t need miracles, they need consistency. And you? You’re already doing better than 90% of people who read this and just scroll past. Keep going. You’re not broken - you’re just learning how to take care of yourself. That’s strength.