Diabetic ketoacidosis, or DKA, isn’t just a scary term you hear in medical dramas. It’s a real, life-threatening emergency that can strike without warning - especially if you have type 1 diabetes, or even type 2 when insulin is missing or failing. Every year, over half a million people in the U.S. end up in the hospital because of it. And while modern medicine can save most people, delay is what kills. The difference between getting help in one hour versus four can mean the difference between recovery and death.

What Happens When Your Body Runs Out of Insulin

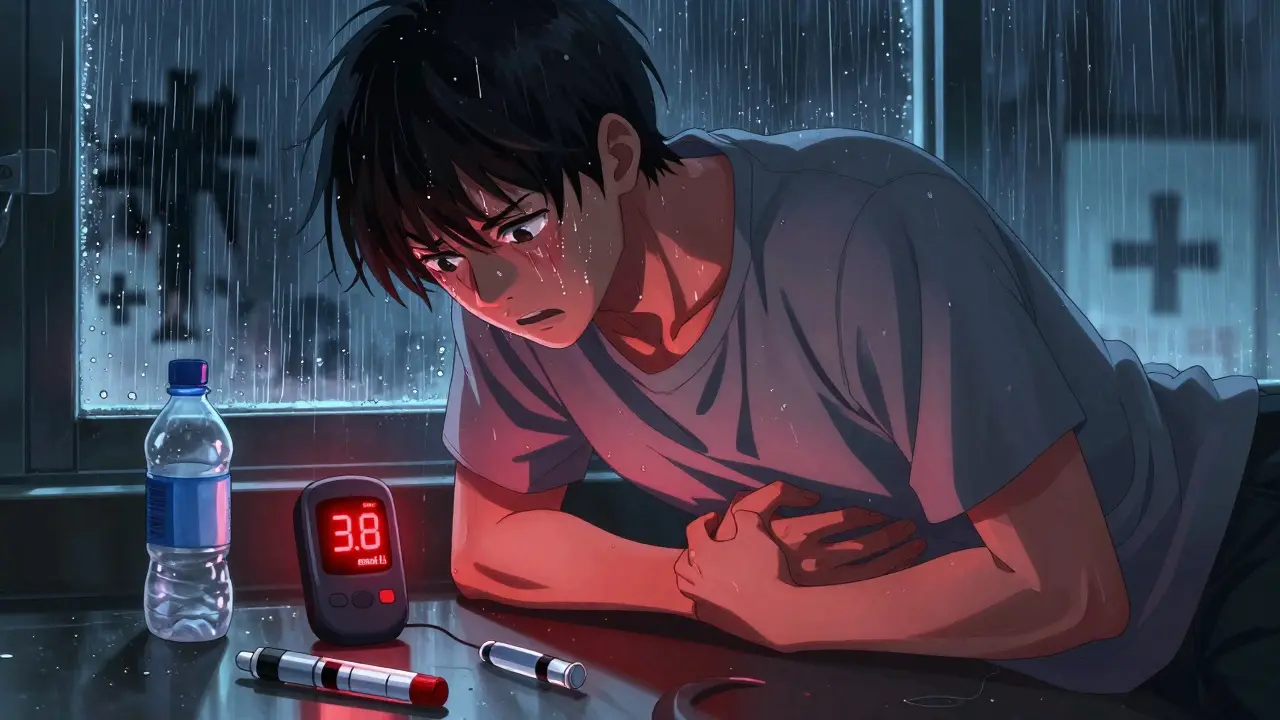

Your body needs insulin to move glucose from your blood into your cells for energy. Without enough insulin - whether because you missed a dose, your pump failed, or you’re newly diagnosed - your body panics. It can’t use sugar, so it starts burning fat instead. That process creates ketones, which are acidic. Too many ketones flood your bloodstream and turn your blood dangerously acidic. That’s DKA.This isn’t a slow burn. It happens fast. Symptoms can start in just a few hours and escalate within 12-24. And here’s the twist: you don’t always have sky-high blood sugar. About 10% of cases are “euglycemic DKA,” where glucose is below 250 mg/dL, often because someone’s on an SGLT2 inhibitor (like Farxiga or Jardiance) and got sick. That’s why just checking glucose isn’t enough.

Early Warning Signs: Don’t Wait for the Worst

The first signs are easy to miss - especially if you think you’re just “feeling off.” But they’re your body screaming for help:- Extreme thirst - drinking 4-6 liters of water a day isn’t normal, it’s a red flag

- Urinating nonstop - more than 3 liters a day, often waking up every hour

- Dry mouth - you feel like your tongue is stuck to the roof of your mouth

- Blood sugar above 250 mg/dL (but don’t wait for this number - act earlier if you feel bad)

If you notice even two of these, especially with high glucose, test your ketones. Use a blood ketone meter - they’re more accurate than urine strips. If your ketones are above 3 mmol/L, you’re in danger. Call your doctor or head to the ER. Don’t wait. Don’t try to “power through.”

Progression: When It Turns Critical

If you ignore the early signs, things get worse - fast.- Nausea and vomiting - not just upset stomach, but persistent, forceful vomiting

- Abdominal pain - often mistaken for food poisoning or appendicitis, especially in kids

- Extreme fatigue - you can’t stand up, walk, or even talk

- Weakness - grip strength drops by 30-40%, something you can feel in your hands

- Fruity-smelling breath - like nail polish remover or overripe apples

- Deep, fast breathing - called Kussmaul respirations - your body’s desperate attempt to blow off acid

- Confusion or disorientation - you can’t think straight, forget where you are

- Drowsiness or unconsciousness - this is a code blue situation

At this point, you’re in the ICU. And if you’re a child or teen, cerebral edema - brain swelling - becomes the biggest threat. It’s rare (0.5-1% of cases) but kills 1 in 5 of those who get it. That’s why fluid management in the hospital is so strict: too much too fast can drown the brain.

What Happens in the Hospital: The Exact Treatment Protocol

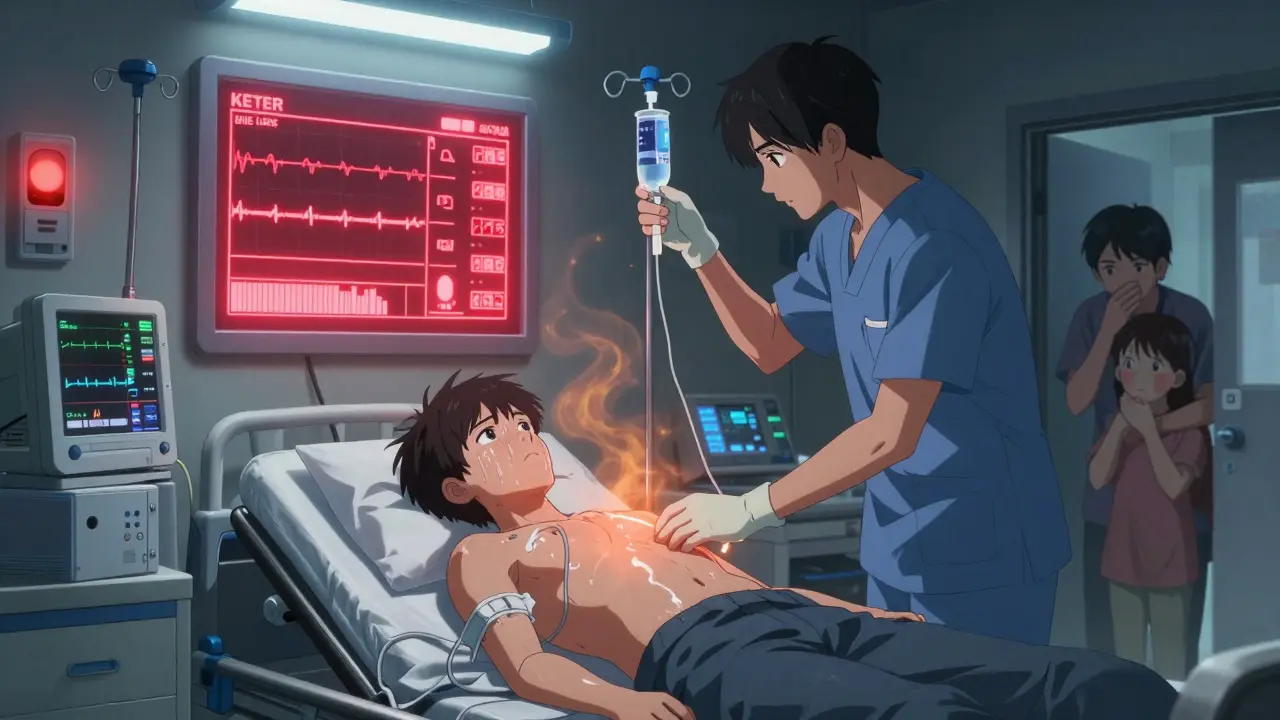

There’s no guesswork in DKA treatment. Hospitals follow strict, evidence-based steps - and they work.First hour: You get fluids. Not just water - 1-1.5 liters of IV saline (0.9% sodium chloride) over 60 minutes. This fixes dehydration, flushes out ketones, and gets your kidneys working again.

Simultaneously: You get insulin. Not a shot. A continuous IV drip. A small bolus (0.1 unit per kg) to start, then a steady drip at the same rate. Blood sugar drops by 50-75 mg/dL per hour. Too fast? Risk of brain swelling. Too slow? DKA keeps advancing.

Electrolytes: Even if your blood potassium looks normal, you’re massively depleted. You’ll get potassium IV - usually 20-30 mEq per hour - because your cells are starving for it. Low potassium can cause deadly heart rhythms.

Bicarbonate? Almost never. Only if your blood pH is below 6.9 - which is extremely rare. Giving bicarbonate in most cases does more harm than good. It can worsen brain swelling and cause low calcium. Most U.S. hospitals still do it wrong - but the guidelines have changed since 2023.

Monitoring: Blood sugar checked every hour. Ketones every 2-4 hours. Electrolytes every 2-6 hours. You’re watched like a hawk. If your pH doesn’t improve after 4-6 hours, they look for hidden triggers - like an infection (50% of cases), a missed insulin dose (30%), or a new diagnosis (20%).

What Gets You Out of the Hospital

You’re not discharged until three things are stable for at least two checks:- Blood ketones under 0.6 mmol/L

- Bicarbonate above 18 mmol/L

- Arterial pH above 7.3

Average hospital stay? 2.5 to 4 days. But if your pH was below 7.0 when you arrived? You’re looking at 3.8 days. If it was 7.0-7.2? Maybe just 2.1 days. That’s why acting fast matters.

And here’s the kicker: if you stop treatment too early - say, because you feel “better” after 24 hours - 12% of people bounce back into DKA within 72 hours. That’s why hospitals keep you until the acid is fully cleared.

What Causes DKA - And Why It’s Rising

Most cases happen because of something preventable:- Infection - pneumonia, UTI, flu - increases insulin needs

- Missing insulin doses - 30% of cases

- Newly diagnosed diabetes - 20% of pediatric DKA cases are the first sign of type 1

- Insulin pump failure - 35% of pump-related DKA is due to clogged infusion sets

- SGLT2 inhibitors - these diabetes pills can trigger euglycemic DKA, even with normal glucose

And the biggest hidden driver? Cost. In the U.S., the average monthly insulin cost is $374. One in four people with type 1 diabetes ration their insulin. That’s not negligence - it’s survival. And it’s why DKA cases are rising 5.3% every year.

How to Prevent It - Real Strategies That Work

You can’t always avoid illness. But you can avoid DKA.- Test ketones when glucose is over 240 mg/dL - every 4-6 hours during illness

- Switch to insulin injections if your pump fails or you’re sick - don’t wait

- Use a continuous glucose monitor (CGM) with ketone alerts - people with Dexcom G7 or similar cut DKA risk by 76%

- Have a sick-day plan - written by your doctor - with clear instructions on insulin adjustments

- Know your emergency contacts - and make sure your family knows the signs too

And if you’re on an SGLT2 inhibitor? Talk to your doctor. These drugs are great for many, but if you have type 1 diabetes, you need to know the risks. Your doctor should have warned you - if they didn’t, ask.

What You Should Do Right Now

If you have diabetes - even type 2 - here’s your action list:- Get a blood ketone meter if you don’t have one. Urine strips are outdated.

- Keep ketone test strips on hand. Don’t wait until you’re sick.

- Teach your partner, parent, or friend the warning signs. Save this article for them.

- Know your insulin pump’s backup plan. What do you do if the infusion set clogs?

- Call 911 or go to the ER if you have vomiting, confusion, or fruity breath - even if your glucose isn’t sky-high.

DKA doesn’t care if you’re “good” with your diabetes. It doesn’t care if you’ve been stable for years. One missed dose, one infection, one broken pump - and you’re in danger. But if you know the signs, act fast, and test ketones - you can stop it before it stops you.

Can you have DKA with normal blood sugar?

Yes. About 10% of DKA cases are called "euglycemic DKA," where blood glucose is below 250 mg/dL. This often happens in people using SGLT2 inhibitor medications (like Farxiga or Jardiance), especially during illness or insulin shortages. Even if your glucose looks fine, if you feel sick and have fruity breath or vomiting, test your ketones. Don’t assume you’re safe just because your meter isn’t flashing red.

How long does it take for DKA to become life-threatening?

DKA can turn deadly in as little as 12-24 hours if untreated. The longer you wait, the worse it gets. Studies show every hour of delay increases mortality risk by 15%. If you have vomiting, confusion, or deep breathing, you’re already in danger. Don’t wait for symptoms to get worse - go to the hospital immediately.

Can insulin pumps cause DKA?

Yes. About 35% of DKA cases linked to insulin pumps happen because of infusion set failures - a clogged tube or dislodged catheter. When the pump stops delivering insulin, your body goes into ketosis within hours. That’s why you should always have backup insulin pens and know how to switch to injections during illness. Never rely on a pump alone when you’re sick.

Why do hospitals give so much IV fluid?

DKA causes severe dehydration - you can lose 5-10 liters of fluid through frequent urination and vomiting. IV fluids restore blood volume, flush out ketones, and help your kidneys and liver recover. Giving too little delays recovery. Giving too much too fast risks brain swelling, especially in children. That’s why fluids are given in controlled, step-by-step amounts - starting with 1-1.5 liters in the first hour, then slowing down.

Is DKA more dangerous for children?

Yes. Children are more likely to develop cerebral edema - brain swelling - during DKA treatment. It happens in 0.5-1% of pediatric cases, but kills up to 24% of those affected. That’s why hospitals use slower fluid rates and avoid bicarbonate in kids. Parents should know that vomiting, confusion, or headaches during DKA treatment are red flags - call the medical team immediately.

Can you prevent DKA with technology?

Absolutely. People using continuous glucose monitors (CGMs) with ketone alerts - like the Dexcom G7 or Abbott Libre 3 - reduce DKA risk by 76%. These devices can warn you 12 hours before DKA develops by spotting rising glucose and ketone trends. Some new systems, like Tidepool Loop, now include AI-driven DKA prediction tools. If you’re on insulin, a CGM isn’t a luxury - it’s a lifesaver.

What should I do if I suspect DKA but can’t get to a hospital right away?

If you’re alone and can’t reach emergency care, give yourself a fast-acting insulin shot (if you have one), drink water, and call 911. Do not wait. Do not try to “wait it out.” Even a single insulin dose can slow progression. But you still need IV fluids and professional monitoring. DKA doesn’t resolve on its own. Delaying care is the biggest risk factor for death.

Wren Hamley

January 2, 2026 AT 21:24Man, I never realized how fast DKA can hit. I had a friend with type 1 who thought he was just dehydrated after a marathon-turned out his pump clogged at mile 18. He was lucid at 7 PM, unconscious by 2 AM. Blood ketones at 5.8. They had to intubate him. Don’t wait for the ‘classic’ signs. If you feel off and your glucose is above 240, grab that ketone meter. No excuses.

Tiffany Channell

January 3, 2026 AT 05:25Of course people are dying-it’s not rocket science. If you can’t afford insulin, you shouldn’t have diabetes. The system failed them, not the disease. Stop romanticizing negligence as ‘survival.’ This isn’t a moral victory, it’s a preventable tragedy caused by poor life choices.

Hank Pannell

January 3, 2026 AT 12:56What’s fascinating is how DKA exposes the fragility of biological homeostasis. Insulin isn’t just a hormone-it’s a metabolic gatekeeper. When it’s absent, the body doesn’t just switch fuels; it enters a state of biochemical chaos where ketogenesis becomes autotoxic. The body’s attempt to compensate via Kussmaul breathing is essentially a last-ditch acid-base emergency response. And yet, we treat it like a checklist. We don’t talk about the epigenetic stress this imposes on pancreatic beta cells in type 2 patients who develop DKA. It’s not just a crisis-it’s a systemic unraveling. We need to reframe this not as a management failure, but as a physiological rebellion.

Kerry Howarth

January 5, 2026 AT 07:48Test ketones early. Keep insulin on hand. Know your pump’s backup plan. Call 911 if you’re confused or vomiting. Simple. Life-saving. Do it.

Michael Burgess

January 6, 2026 AT 15:11Just had my Dexcom G7 ping me at 3 AM-ketones rising, glucose at 280. I hit a fast-acting shot, chugged water, and called my endo. By 5 AM, ketones were down to 0.9. That CGM saved me from a hospital trip. Seriously, if you’re on insulin and don’t have a CGM with ketone alerts, you’re playing Russian roulette with your kidneys and brain. This tech isn’t fancy-it’s a seatbelt. And yeah, I cried when I got the alert. Not because I was scared-I was grateful. This shit works.

Haley Parizo

January 7, 2026 AT 12:37Let’s be real-DKA isn’t just about insulin. It’s about capitalism. The fact that someone has to ration life-saving medication because Big Pharma prices it like a luxury car? That’s not medical negligence. That’s state-sanctioned murder. And the system blames the patient? No. The system is the disease. Every time someone dies from DKA because they couldn’t afford insulin, it’s not an accident. It’s policy. And we’re all complicit.

Joy F

January 8, 2026 AT 16:22I’ve been living with type 1 for 22 years. I’ve had DKA twice. The first time, I was 17 and thought I could ‘tough it out.’ Woke up in the ICU with a 6.8 pH. My mom screamed so loud the nurses came running. The second time? I was 34, on Farxiga, felt ‘fine’-glucose was 210. Ketones hit 4.1. I called 911 before I even sat up. That’s the difference between trauma and survival. And now? I have a laminated card in my wallet that says: ‘IF YOU SMELL LIKE APPLES, CALL 911.’ My kids know what it means. My dog knows. Even my barista knows. DKA doesn’t care if you’re ‘good’ with your numbers. It only cares if you’re listening.

Lori Jackson

January 10, 2026 AT 02:09How is it still 2024 and people don’t know that urine ketone strips are obsolete? I mean, really. It’s like using a slide rule to calculate rocket trajectories. Blood ketone meters cost $15 a strip-less than a latte. If you’re still relying on those pink paper strips, you’re not just uneducated-you’re endangering lives. And if your doctor hasn’t updated you on euglycemic DKA? Find a new one. This isn’t 2010 anymore.

Angela Fisher

January 10, 2026 AT 19:19Okay, but what if this is all a lie? What if DKA isn’t real? I read a forum where someone said the whole thing was invented by pharmaceutical companies to sell insulin and CGMs. They said the ‘fruity breath’ is just from eating too much fruit, and ‘Kussmaul breathing’ is just anxiety hyperventilation. And why do hospitals give so much IV fluid? Maybe they’re just trying to make you stay longer to bill more. I’ve got a cousin who ‘got better’ with lemon water and prayer. And now he’s hiking in Patagonia. So… maybe we’re being manipulated? I’m not saying it’s true-but what if?

Ian Detrick

January 11, 2026 AT 06:13My brother’s a paramedic. He told me about a kid, 14, found unconscious in his bedroom. No insulin in the house. Mom was working two jobs. The kid had been skipping doses to make the insulin last. They got him to the hospital in 90 minutes. He survived. But he’s got brain damage now. Not from DKA. From delay. That’s the real horror-not the ketones. It’s the silence. The shame. The fear of asking for help. We need to talk about this like it’s a public health fire drill. Not a medical footnote.