Opioid Risk Calculator

Calculate Your Opioid Risk

This tool estimates your risk of opioid-induced breathing problems during sleep based on your current dosage and other sedatives. The higher your risk, the more important it is to discuss with your doctor.

When you take opioids for pain, you’re not just managing discomfort-you’re putting your breathing at risk, especially while you sleep. This isn’t a rare side effect. It’s a silent, life-threatening danger that affects tens of thousands of people every year. If you or someone you know is on long-term opioid therapy and wakes up gasping for air, feels exhausted in the morning, or has been told they stop breathing during sleep, this is not normal. It’s opioid-induced respiratory depression-and it’s worsening sleep apnea in ways most doctors still don’t fully address.

How Opioids Shut Down Your Breathing at Night

Opioids don’t just dull pain. They directly interfere with the brain’s breathing control centers. The key areas affected are the parabrachial complex and the pre-Bötzinger complex-two clusters of neurons deep in the brainstem that keep your breathing steady, even when you’re asleep. When opioids bind to mu-opioid receptors in these regions, they slow down the signals that tell your lungs to inhale and exhale. The result? Longer pauses between breaths, shallow breathing, and sometimes complete stops in breathing that last 10 to 30 seconds or more.This isn’t just obstructive sleep apnea, where your airway collapses. This is central sleep apnea-your brain literally forgets to tell your body to breathe. Studies show that people on high-dose opioids (100 morphine milligram equivalents or more daily) average nearly 16 breathing pauses per hour during sleep. Compare that to non-users, who average fewer than 5. That’s a threefold increase in dangerous events.

And it gets worse. Opioids also weaken the muscles that hold your airway open, especially the genioglossus muscle in your tongue. In animal models, this muscle’s activity drops by 40 to 60%. So even if your brain sends the signal to breathe, your airway might still collapse. You’re caught between two failures: your brain doesn’t command breathing, and your throat muscles can’t keep the passage open.

Why Sleep Makes It Worse

Sleep isn’t just a passive state. It’s when your body’s natural defenses against breathing problems turn off. When you’re awake, your brain has extra signals-called “wakefulness drive”-that keep your breathing strong. Once you fall asleep, those signals fade. Opioids remove the backup system. Without wakefulness drive, your breathing becomes fragile. A single pause can turn into a chain reaction: low oxygen → increased carbon dioxide → brain panic → gasping wake-up → disrupted sleep → next night, the same thing happens again.People on opioids often report unrefreshing sleep, morning headaches, and daytime fatigue. These aren’t just complaints-they’re signs of chronic low oxygen at night. Over time, this strain on your heart and lungs increases the risk of high blood pressure, heart attacks, and stroke. A 2021 study in the American Journal of Respiratory and Critical Care Medicine found that 30 to 40% of chronic opioid users develop clinically significant sleep-disordered breathing. Many don’t even realize it until they’re hospitalized after an overdose.

The Parabrachial Complex: The Main Culprit

Research from Harvard and Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center has pinpointed one area as the biggest problem: the parabrachial complex, especially the Kölliker-Fuse nucleus. This part of the brainstem controls how long you exhale. When opioids activate receptors here, expiration becomes abnormally long-sometimes doubling or tripling. That’s why people on opioids don’t just breathe slowly; they take long, drawn-out breaths followed by long pauses. In mouse studies, removing opioid receptors from just this one area reduced breathing pauses by 75 to 80%.That’s a game-changer. It means the problem isn’t just in the breathing rhythm generator (the pre-Bötzinger complex). It’s in the timing controller. Targeting this region could lead to new drugs that preserve pain relief without stopping your breathing. But here’s the catch: the parabrachial complex also helps process pain signals. So any drug that blocks opioid effects here must be extremely precise-or you’ll lose pain control.

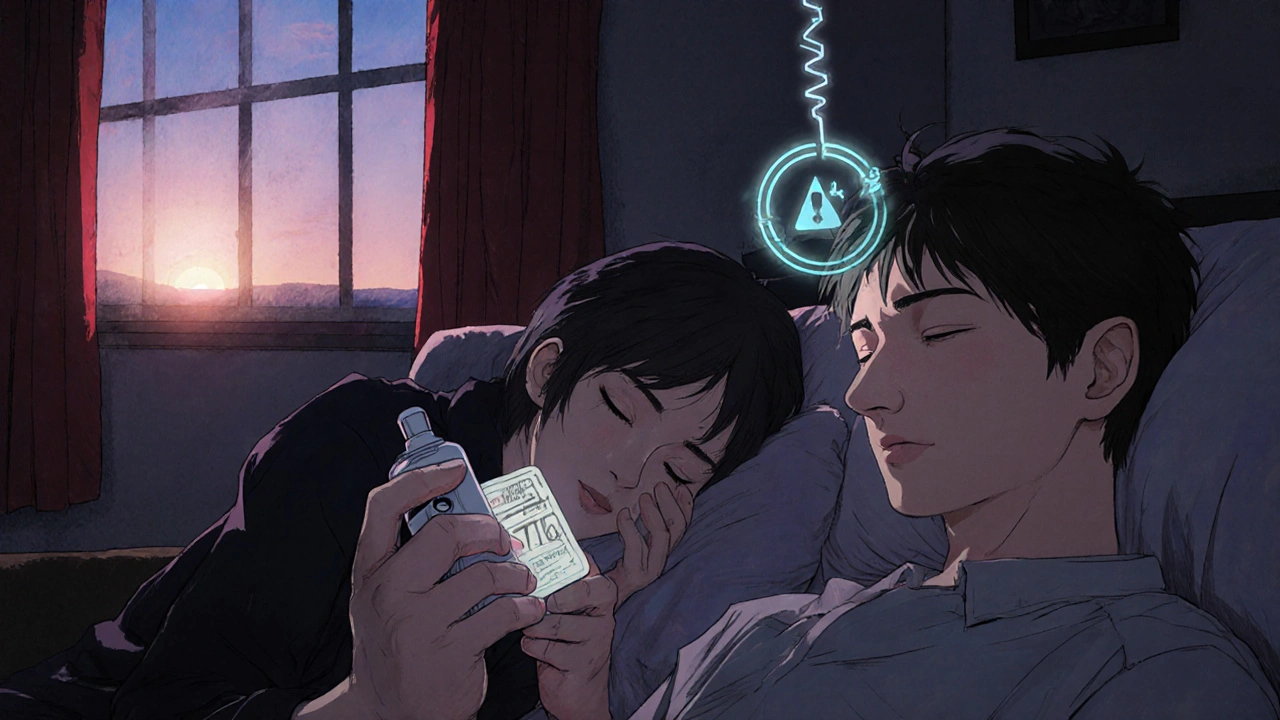

Combining Opioids With Other Drugs Is a Deadly Mix

If you’re on opioids and also take benzodiazepines (like Xanax or Valium), sleep aids, muscle relaxers, or even alcohol, your risk of fatal respiratory depression jumps by 300 to 500%. These drugs all depress the central nervous system. Together, they amplify each other’s effects. A 2023 CDC report showed that nearly 70% of opioid overdose deaths involved another sedative. That’s why doctors are now trained to ask: “Are you taking anything else that makes you sleepy?” If the answer is yes, they should reconsider the opioid prescription-or at least reduce the dose.Even over-the-counter sleep aids can be dangerous. Diphenhydramine (Benadryl) and doxylamine (Unisom) are common in nighttime remedies. They’re not opioids, but they slow breathing. For someone already on oxycodone or hydrocodone, that’s enough to tip the balance.

What You Might Not Realize: Pulse Oximeters Can Lie

Many people think if their oxygen level looks normal on a finger monitor, they’re fine. But that’s misleading. Oxygen saturation can stay above 90% even while you’re hypoventilating-because your body is compensating by breathing harder when awake, or because your lungs are still exchanging some oxygen during brief pauses. The real danger happens in the gaps: when your carbon dioxide rises, your brain doesn’t respond, and you slip into unconsciousness without warning.Capnography-measuring carbon dioxide in exhaled air-is the gold standard for detecting early respiratory depression. But it’s rarely used outside hospitals. In outpatient settings, less than 20% of primary care providers screen for sleep apnea in opioid users. That’s a massive gap in safety.

What Can Be Done? Screening, Reversal, and Future Hope

If you’re on long-term opioids, you need a sleep study. Not because you snore-but because your brain might be failing to control your breathing. The American Society of Anesthesiologists recommends baseline sleep studies for anyone on chronic opioid therapy, especially if they have obesity, a history of snoring, or daytime sleepiness.Naloxone (Narcan) is the only approved reversal agent. It works by kicking opioids off their receptors. But timing matters. Too little, and it doesn’t work. Too much, and it triggers severe withdrawal-sweating, vomiting, panic, and pain. The right dose is 0.04 to 0.4 mg intravenously, repeated every 2 to 3 minutes if needed. For home use, nasal naloxone kits are available, but they’re underused. Only 1 in 5 people on high-dose opioids have a prescription for naloxone at home.

On the horizon, researchers are testing new drugs that target breathing without touching pain relief. Ampakines and 5-HT4(a) agonists have improved breathing in animal studies by 40 to 60% without reducing pain control. One promising approach is “biased agonists”-opioid-like drugs that activate pain pathways but avoid the ones that shut down breathing. Early lab results show 70 to 80% of pain relief with only 20 to 30% of the respiratory depression. If this works in humans, it could change everything.

Genetic Risk: Why Some People Are More Vulnerable

Not everyone on opioids develops severe breathing problems. Why? Genetics. A variation in the OPRM1 gene-responsible for how your body responds to opioids-can make you more sensitive to respiratory depression. People with certain versions of this gene have naturally weaker breathing responses to high carbon dioxide levels. That means even a standard pain dose can push them into danger. In the next five years, genetic screening for this variant may become routine before prescribing opioids. For those at high risk, non-opioid alternatives like gabapentin, physical therapy, or nerve blocks may be safer first choices.What You Should Do Right Now

- If you’re on opioids and wake up gasping, choking, or feeling like you can’t breathe-get evaluated for sleep apnea. Ask for a polysomnogram.

- Don’t mix opioids with alcohol, benzodiazepines, or sleep aids. Even one extra pill can be deadly.

- Ask your doctor if you should have a naloxone kit at home. Keep it with you, and make sure someone you live with knows how to use it.

- If you feel excessively tired during the day, have morning headaches, or your partner says you stop breathing at night-don’t ignore it. These aren’t just “side effects.” They’re warning signs.

- If you’re a caregiver for someone on opioids, learn the signs of overdose: slow or shallow breathing, blue lips, unresponsiveness. Call 911 immediately. Don’t wait.

The opioid epidemic didn’t end with prescription limits. It evolved. Now, the hidden danger is in the quiet hours-when you’re asleep, and your body can’t fight back. Understanding how opioids affect breathing isn’t just academic. It’s the difference between waking up tomorrow-and not.

Can opioids cause central sleep apnea?

Yes. Opioids suppress the brain’s breathing centers, leading to central sleep apnea-where your brain fails to send signals to breathe during sleep. This is different from obstructive sleep apnea, where the airway collapses. Central apnea caused by opioids is dose-dependent and worsens with higher doses or when combined with other sedatives.

Is sleep apnea worse with opioids?

Absolutely. Opioids don’t just cause sleep apnea-they make existing apnea significantly worse. Studies show people on high-dose opioids have nearly four times more breathing pauses per hour than non-users. They also experience longer pauses, lower oxygen levels, and more frequent awakenings, leading to chronic fatigue and increased cardiovascular risk.

Can naloxone reverse opioid-induced sleep apnea?

Naloxone can reverse the respiratory depression caused by opioids, including during sleep. It works by blocking opioid receptors in the brainstem, restoring breathing signals. However, it’s most effective when given during an active episode of apnea or overdose. It doesn’t prevent apnea from returning once it wears off, so it’s not a long-term solution-just an emergency tool.

Should I get a sleep study if I’m on opioids?

Yes-if you’re on long-term opioid therapy, especially at high doses, a sleep study is strongly recommended. Many people don’t realize they have opioid-induced central sleep apnea until they experience serious complications. Screening can catch it early, allowing for safer pain management or interventions like CPAP or BiPAP.

Are there safer alternatives to opioids for pain?

Yes. For many types of chronic pain, non-opioid options like physical therapy, nerve blocks, gabapentin, antidepressants (like duloxetine), or nonsteroidal anti-inflammatories can be effective with fewer risks. Emerging treatments like dorsal root ganglion stimulation and cognitive behavioral therapy for pain also show promise. Always discuss alternatives with your doctor before starting or continuing opioids.

How do I know if my opioid dose is too high for my breathing?

Warning signs include frequent nighttime awakenings, morning headaches, excessive daytime sleepiness, loud snoring, or being told you stop breathing while asleep. A dose above 90 morphine milligram equivalents per day significantly increases risk. If you’re on 100+ MME daily, you should be screened for sleep apnea and have a naloxone kit available. Never increase your dose without medical supervision.

Rashmi Mohapatra

November 8, 2025 AT 13:51so like... i been on oxycodone for 3 yrs n my husband swears i stop breathin at night but i thought it was just snorin 😅 now i’m paranoid af n gonna book a sleep study tmrw. thanks for the kick in the pants.

Abigail Chrisma

November 9, 2025 AT 21:01This is such an important post. I work with chronic pain patients and I’m always shocked how rarely providers screen for opioid-induced central apnea. It’s not just about addiction-it’s about basic physiology. If you’re on opioids long-term, your sleep study should be as routine as your blood pressure check. We’re failing people by normalizing exhaustion and morning headaches.

Also-naloxone at home isn’t just for overdose. It’s for breathing emergencies during sleep. If your doctor won’t prescribe it, ask for a referral to pain management. You deserve to sleep safely.

Meghan Rose

November 10, 2025 AT 03:50Actually, most of this is overstated. The studies cited are mostly on high-dose users-like 100+ MME-which is already rare. Most people on 20-40 MME don’t have significant central apnea. And let’s be real: if you’re waking up gasping, it’s probably obstructive sleep apnea from weight or anatomy, not opioids. Stop scaring people into thinking every pain pill is a death sentence.

Also, capnography? In outpatient settings? That’s a joke. No primary care doc has that equipment. You’re asking for magic.

Steve Phillips

November 11, 2025 AT 10:36Oh, so now we’re blaming the brainstem? 😏 The parabrachial complex? Kölliker-Fuse nucleus? Please. This reads like a neuropharmacology textbook that got lost in a Reddit thread. Opioids slow breathing. That’s it. You don’t need a 12-page neuroscience deep-dive to understand that mixing Xanax + hydrocodone = bad idea. And no, your pulse oximeter isn’t “lying”-it’s just not measuring what you’re terrified of. You want real data? Get a sleep study. Stop reading 2021 papers and start living.

Also-‘biased agonists’? That’s not science. That’s sci-fi marketing.

Rachel Puno

November 13, 2025 AT 07:48YOU ARE NOT ALONE. If you're reading this and you're tired all the time-your body is screaming. Don't brush it off. Don't wait for your doctor to bring it up. Book that sleep study. Ask for naloxone. Tell your partner to watch you at night. You're worth more than another morning of foggy-headed exhaustion. This isn't weakness. This is awareness. And awareness saves lives 💪❤️

Clyde Verdin Jr

November 15, 2025 AT 01:26So... opioids = death in your sleep? 😭😭😭 I'm just here wondering if my cat is judging me for taking my 15mg oxycodone before bed... like... is she plotting my demise? 😅 I mean, I don't snore, but I do drool. Is that a sign? 🤔

Key Davis

November 16, 2025 AT 07:23While the emotional urgency of this post is commendable, the scientific rigor must be maintained. The assertion that 30 to 40 percent of chronic opioid users develop clinically significant sleep-disordered breathing is derived from heterogeneous cohorts, many of which include patients with pre-existing obesity or cardiopulmonary comorbidities. Without proper multivariate adjustment, the causal attribution to opioids alone remains speculative. Furthermore, the recommendation for universal polysomnography in all long-term opioid recipients may not be cost-effective or clinically justified without stratification by risk factors. A measured, evidence-based approach is imperative.

Cris Ceceris

November 16, 2025 AT 21:34It’s wild to think that our brains have these little switches-like a breathing autopilot-that opioids just flip off. Like, we evolved to breathe without thinking... but now a molecule from a poppy can make us forget how to live. And the worst part? We don’t notice until it’s almost too late. We’re so good at ignoring our bodies until they scream. Maybe pain isn’t the real enemy here. Maybe it’s how we treat the body like a machine we can tweak without consequences.

What if the solution isn’t just better drugs... but a better relationship with our own biology?

Brad Seymour

November 18, 2025 AT 17:05Love this post. Seriously. As someone who’s watched a friend nearly die from this exact thing, I wish everyone on opioids read this. I told my mate to get tested-he laughed. Then he woke up blue last month. Naloxone saved him. Now he’s on gabapentin and sleeping like a baby. Don’t be the guy who ignores the signs. Get checked. Keep the kit. Live.